The World of Whisky (part 1)

Next Saturday is the third Saturday in May, which can only mean one thing.

It’s World Whisky Day!

But you knew that didn’t you?

For once, I’ve got my act together ahead of time, and would like to share all things whisky (or is that whiskey?) with you and still give you time to get any new glasses that you may need.

Let’s start at the very beginning (a very good place to start, according to Julie Andrews).

What is whisky?

Officially, “Whisky is a distilled alcoholic beverage made from fermented grain mash. Various grains (which may be malted) are used for different varieties, including barley, corn, rye and wheat.

Whisky is typically aged in wooden casks, which are typically made of charred white oak. Uncharred white oak casks previously used for the aging of port, rum or sherry are also sometimes used. It is a strictly regulated spirit worldwide with many classes and types.

The typical unifying characteristics of the different classes and types are the fermentation of grains, distillation, and aging in wooden barrels.”

Is it whisky or whiskey?

Like a lot of things associated with the water of life, it’s complicated. In Scotland, Canada and Japan, it’s whisky. Whilst in Ireland and the USA it’s whiskey.

Why the different spellings?

Well, to answer that we need to travel back in time to 1870. During this time Scottish whisky wasn’t of the high quality and excellence you know today. In fact, Scottish whisky was so bad that the Irish whisky distilleries wanted a way for people to differentiate between their whisky and the poor-quality Scottish whisky.

A lot of Irish whisky was exported to America, so to avoid confusion with Scottish whisky the Irish started adding an “e” so that their bottles read “Irish Whiskey." Additionally, around this time, many Irish immigrants began setting up their stills in America, causing the "whiskey" spelling to spread rapidly across the States. The American people quickly adopted the term “whiskey” and have continued to use it ever since.

For the sake of clarity, I’m going to use “whisky” from now on, unless referring specifically to Irish or American drinks (even though it will have my Irish forebears spinning in their graves).

Where did whisky originate?

Seems like an easy question. Where does whisky come from? Alas, it’s not really, definitively, known, because it’s whiskey, aka whisky, aka uisge beatha or uisge baugh (the water of life in Irish and Scottish Gaelic, respectively) aka aquavitae.

The main argument rages (to this day) between the Scots and the Irish, both of whom have variously claimed to have invented it.

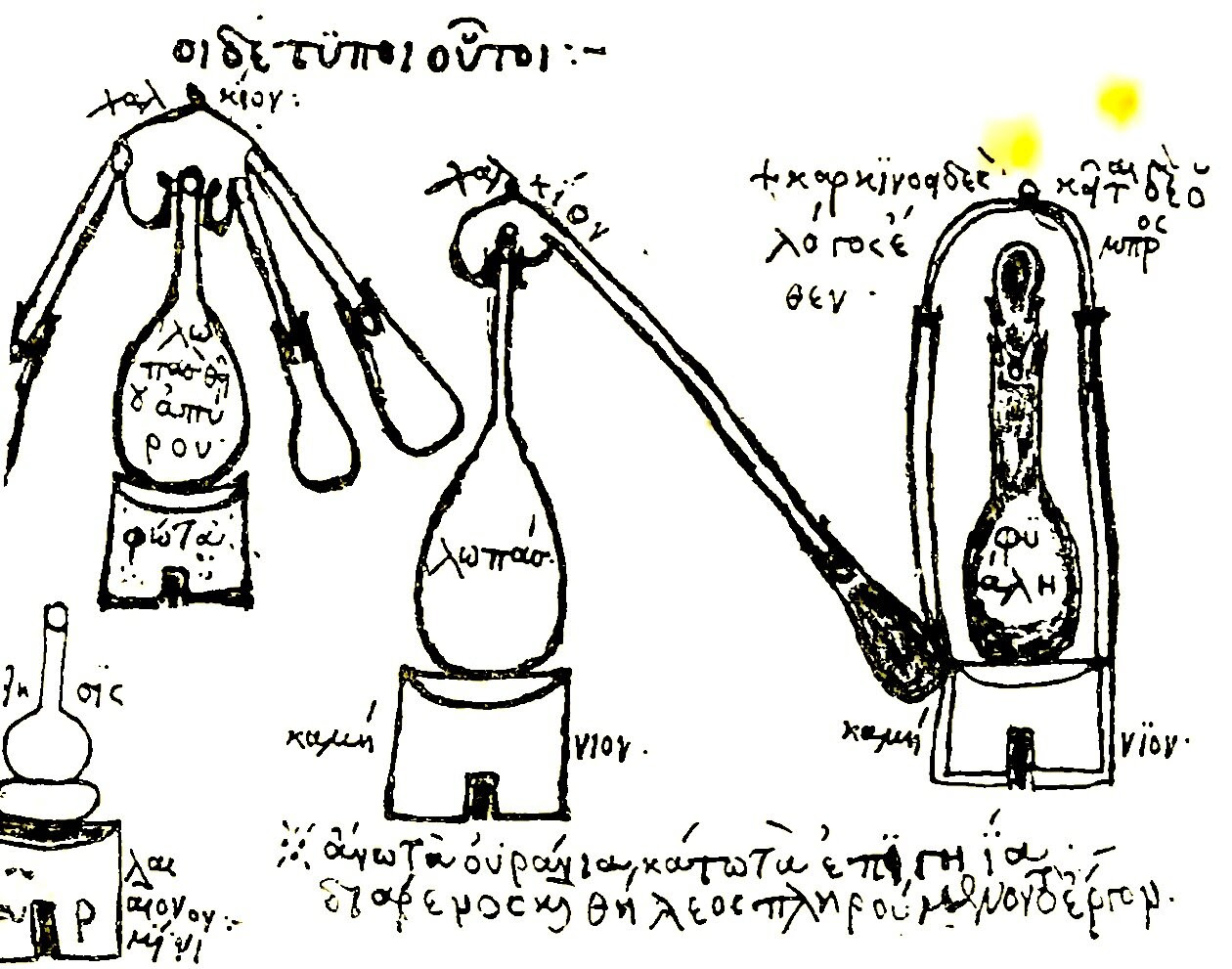

|

The Irish claim that early Christian Irish monks returning from Arabia around 600 A.D. brought back with them the secrets of distillation (which originated in the Middle East) and made Ireland a very happy country.

And some stories have it that the Irish actually introduced the art of distilling to Scotland, where, to say the locals embraced it is something of an understatement.

The first written record of “whisky” appears in the Irish Annals of Clonmacnoise in 1405, where it was written that the head of a clan died after “taking a surfeit of aqua vitae” at Christmas. (Hmm… seems familiar!)

Another one of the oldest references to whisky occurs in the Scottish Exchequer Rolls for 1494, where there is an entry of ‘eight bolls of malt to Friar John Cor wherewith to make aquavitae’. A boll was an old Scottish measure of not more than six bushels. (One bushel is equivalent to 25.4 kilograms) As this is well over a tonne of malt, presumably, whisky making was fairly well established!

One of the earliest references to “uiskie” occurs in the funeral account of a Highland laird about 1618. It’s not a huge leap to get “uiskie” from the Gaelic “uisge”. Although, a royal licence was granted to the Old Bushmills Distillery in Northern Ireland to distil whisky ten years earlier, which makes it the oldest licensed distillery in the world.

Up until this point, distilling had been a cottage industry, with farmers and monasteries producing enough for their own, and their neighbours’, consumption. The increasing popularity of Scotch attracted the attention of the Scottish Parliament, who, looking to profit from the fledgling industry, introduced the first taxes on whisky in 1644. This led to an increase in illicit whisky distilling across Scotland.

In 1707, the Acts of Union took effect, and the Kingdoms of Scotland and England were merged, to create Great Britain. The Government attempted to control whisky production by introducing a series of taxes.

In 1725, parliament introduced a malt tax which presented a huge threat to the small-scale, cottage industry of whisky production. Scottish and Irish distillers largely responded by dodging the tax, and whisky production became even more of an illicit industry, with many producers heading underground and working at night to disguise the smoke that their fires created. This gave whisky one if its first, and finest, nicknames, you guessed it! “Moonshine.”

In Ireland, the introduction of a tax on whisky production crippled its legal industry. Licenced distillers of “parliament whiskey” (whisky legally produced under licence) plummeted from 1,228 in 1779, to 246 in 1780. This meant that the production of ‘poteen’ (whisky’s illegal counterpart) flourished. In fact, poteen was often regarded as being of a higher quality than ‘parliament whiskey’, due to the pressures licenced distilleries were under to churn out their products and make a profit.

By 1882 there were a mere 40 legal distilleries in the whole of Ireland, whereas, it is believed that in the Donegal region alone, there were 800 illicit stills producing whiskey.

Other notable events along whisky’s timeline include:

1820 - A certain Scottish grocer named John Walker began producing his own whisky, which would become one of the most famous, most widely distributed and best selling brands of Scotch whisky in the world. Selling over 150 million litres every year.

Indeed, Johnnie Walker Red Label was Winston Churchill's favourite whisky, which he mixed with a large amount of water and drank throughout the day.

In October 2021, Johnnie Walker announced a new label, Jane Walker, created by the distillery's first female master blender. The famous Johnnie Walker Striding Man, which has been in continuous use since 1909, was replaced on the label by a striding woman.

Johnnie Walker himself, was teetotal.

|

1831 - After inventing a “continuous still” and improving the technology involved in distillation, Irish inventor Aeneas Coffey patented the Coffey still, allowing manufacturers to produce whiskey more efficiently, and at a lower cost.

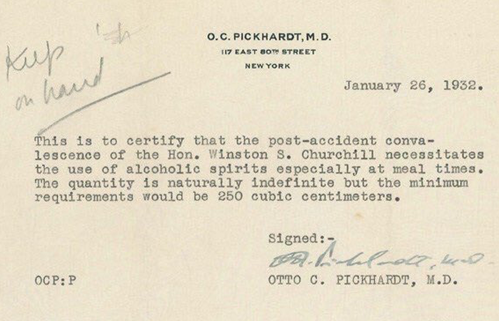

· 1920-1933 - For 13 years, American Prohibition banned all production, sale, and use of alcohol. However, the federal government made one exception: the prescription of medicinal whiskey from a doctor, to be sold through a licensed pharmacy. (coincidentally, during this same timeframe, the pharmacy chain Walgreens grew from 20 stores to nearly 400!)

Winston Churchill's "prescription" that allowed him at least half a pint of whisky a day when visiting the US during Prohibition.

How is whisky made?

It won’t surprise you to know that it varies, depending on the style being made, the country where it originates, and other factors, but the general process remains the same in most cases.

Malting

All whisky starts as raw grain—in the case of malt whisky this is barley, which has to be specially treated to get to its sugars. The barley is moistened and allowed to partially sprout, or germinate, which produces an enzyme that converts the barley's starches to sugars. Germination is then cut off by heating, which dries the barley.

Mashing

The sugars contained in the grain must be extracted before fermentation, and this is done by mashing. The grains that are being used, be they barley, corn, wheat, or rye, are ground up, put in a large tank (called a mash tun or tub) with hot water, and agitated. Even if the distiller isn't making malt whisky, some ground malted barley is typically added to help catalyse the conversion of starches to sugars. The resulting mixture resembles porridge. Once as much sugar as possible has been extracted, the mixture, now known as mash (or wort if strained of solids) moves on to the fermentation stage.

Fermentation

Fermentation happens when the mash/wort meets yeast, which gobbles up all the sugars in the liquid and converts them to alcohol. This takes place in giant vats and can take anywhere from 48 to 96 hours, with different fermentation times and yeast strains resulting in a spectrum of different flavours. The resulting beer-like liquid, called distiller's beer or wash, is around 7%-10% ABV before it goes into the still.

Distillation

The process of distilling increases the alcohol content of the liquid and brings out volatile components, both good and bad. Stills are usually made of copper, which helps strip spirits of unwanted flavour and aroma compounds. The two most common types of stills are pot stills and column stills which function differently. Both are outlined below.

Pot Still Distillation

Pot stills are used in the production of whiskies (usually, though not always, malt whiskies) from Scotland, Ireland, the United States, Canada, Japan, and elsewhere. Pot still distillation is a batch process. Some styles use double-distillation, while others are distilled three times. The wash goes into the first still, where it's heated up. Alcohol boils at a lower temperature than water, so the alcohol vapours rise off the liquid and into the still neck and eventually reaches the condenser, which turns them back to liquid. The resulting liquid, (which is about 20% ABV) goes into the second still, where the process is repeated. At this time, a third distillation can occur. The resulting final spirit comes off the still starting at around 60%-70% ABV. The distiller discards or reserves a certain amount of spirit from the beginning and end of the run, known as heads and tails, due to their unwanted flavours and aromas. The rest, known as the heart, goes into barrels for ageing.

|

Column Still Distillation

Column stills, also known as continuous or Coffey stills, are typically used to produce bourbon, rye, and other American whiskeys, as well as grain whiskies from Scotland, Ireland, Canada, Japan and elsewhere. The column still works continuously and efficiently, removing the need for the batch process of pot stills. The distiller's beer is fed into the column still at the top and begins descending, passing through a series of perforated plates. Simultaneously, hot steam rises from the bottom of the still, interacting with the beer as it flows downward, separating out the solids and unwanted substances, and pushing up the lighter alcohol vapours. When the vapours hit each plate, they condense, which increases the alcohol content. Eventually, the vapor is directed into a condenser. Column stills can produce spirit up to 95% ABV, although most whiskies are distilled to lower proofs.

|

Maturation

Nearly all whiskies are aged in wood, usually oak, containers. One notable exception is corn whiskey, which may be aged or unaged. Bourbon, rye, and other types of American whiskey must be aged in new charred oak barrels, while for other countries' styles, the type of oak and its previous use are generally left up to the producer. Barrels are stored, and as the whisky matures, some of the alcohol evaporates: This is known as the angels' share, and it creates a distinct (and lovely) smell. Some whiskies, such as scotch, have a required minimum age.

Bottling

Once matured, whisky is bottled at a minimum of 40% ABV. The whisky may be chill-filtered or filtered in another way to prevent it from becoming cloudy when cold water or ice is added. For most large whisky brands, a bottling run combines a number of barrels, anywhere from a few dozen to hundreds, from the distillery's stock. When only one barrel is bottled at a time, it's labelled as single cask or single barrel.